There’s a plan for that…

A small group of NHS managers draw up, test and implement the plans that protect us and the health service from the worst effects of disasters, terrorist attacks and pandemics. We talk to Dr Chloe Sellwood, deputy head of emergency preparedness, resilience and response (EPRR) for NHS England London region, about thinking the unthinkable and working on the frontline of emergency response.

Craig Ryan: Let’s start with the most basic question. What is an emergency? What defines what you plan for?

Chloe Sellwood: That’s a really good question. Essentially, it’s anything that could cause, or is causing, harm or disruption to the UK, and for us specifically, to NHS patients, staff or premises. It’s something that needs an intervention above and beyond normal business. So, normal winter pressures, flu and so on, are not an emergency per se, as we face them routinely, but an unexpected snowfall or a major norovirus outbreak would need to be managed under extraordinary—yet planned—arrangements.

Are the scenarios set nationally, or do you come up with your own ideas about all the terrible things that could happen in London?

The UK National Risk Register identifies scenarios based on potential impact and potential likelihood. Scenarios are typically divided into “threats” and “hazards”—hazards being naturally occurring, threats being manmade.

We have national and regional work plans for dealing with things like CBRN [chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear], mass casualties and mass fatalities. Each region has to think about what the threat means to them. A major terror attack would potentially be much easier to manage here in London than in Cornwall, where there is a greater distance between hospitals and intensive care beds. That said, something like that is arguably more likely to happen in London than in Penzance.

It’s hard to think of a civil emergency that wouldn’t affect the NHS, so you must be involved in most of these scenarios.

Yes, but different partners lead on different risks. So, mass fatalities would generally be led by local authorities and the police because they’re dealing with body storage, body identification and that sort of thing, whereas casualties would be very much NHS. Not to be flippant, but we’re more interested in people when they’re still alive!

Photo: © Jackie King

Photo: © Jackie King

Do you deal with floods or are they now too frequent to count as an emergency?

Floods are absolutely up there and of increasing concern as climate change evolves. Under Local Resilience Forum arrangements, the Environment Agency is leading a review of flood plans, working with local authorities and other partners to understand the impact of what’s going on.

There are generic and specific plans for dealing with the flood itself and its indirect impact on the NHS. So, for example, if your emergency department is flooded, you can’t see patients. If the flood disrupts transport networks, your staff can’t get in, clinical waste can’t get taken away and supplies can’t be delivered. Or if there’s a mass evacuation, you will have displaced people who potentially need NHS support.

And I suppose terrorism is always high on your agenda?

Yes, I think back to 2017 when we had the attacks on London Bridge, Westminster Bridge and the Manchester arena, as well as less well-remembered incidents at Finsbury Park mosque and Parsons Green tube. In the NHS, we’re thinking about supporting casualties, staff, first responders, people who got caught up in it, and even people who were involved in something previously and had memories triggered. The Westminster Bridge attack lasted about 20 seconds, but four years later support is still needed for people who were involved.

And cyber terror poses a different kind of threat—to the NHS as an institution.

Yes, the WannaCry attack, also in 2017, was incredibly disruptive and challenging for the NHS. Our role in NHS England is to strategically, command, coordinate, support and oversee the London regional response. There are individual teams managing the situation in each hospital trust, in primary care, and the ambulance service.

For us, it was very much about sharing what we knew about what was happening and the mitigations being developed to bring computer systems back online safely. And just making sure there was a consistent and supportive message to staff and patients about the disruption to healthcare services and how access the care they needed.

Apart from Covid, what new threats have emerged in recent years?

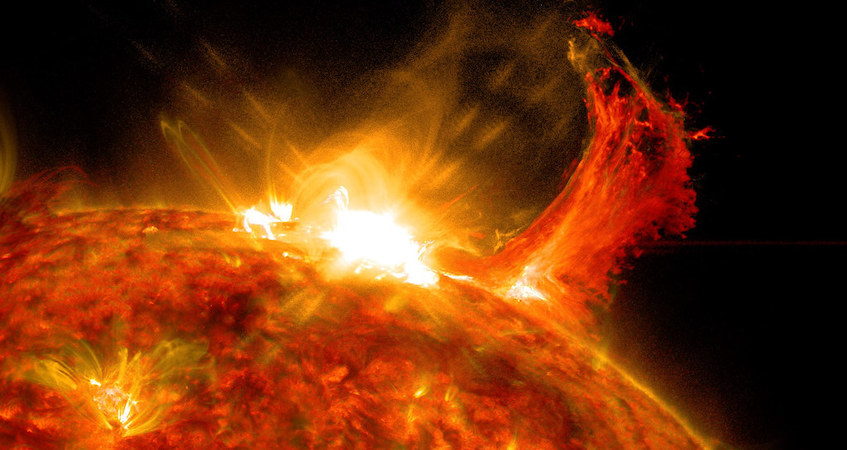

One that’s an interesting challenge is ‘space weather’ (see box below). That could be a coronal mass ejection from the sun, causing a massive electromagnetic pulse that knocks out electricity grids and fries everything in your phone. That appeared on the National Risk Register a few years ago and everyone thought, mmm, okay, now what?

Wow, space weather! How do you even begin to plan for that?

Generally, there’s an existing plan you can use as a starting point, because there’s basically four generic disruptions in the NHS: not enough staff, too many patients, you haven’t got the building or you haven’t got the kit. So we look at plans for loss of staff and power disruption—we know people will be stuck in lifts or halfway through surgery, for example.

We look at business continuity plans for individual organisations. But it’s very much a partnership approach—Covid brought starkly into focus that the NHS is only as strong as social care, for example. We work with the London Resilience Partnership on what scenarios mean for London as a whole. At the same time, trusts like Guy’s and St Thomas’ work with Lambeth and Southwark councils, and relevant public and private-sector bodies in their area.

Once we’ve got a draft policy, we ask people, “Is there anything ridiculous in this? Does it broadly make sense?” And when we think it’s worth using, we train and then exercise to test the plan. That could be as simple as a facilitated workshop where we talk through the plan and discuss any concerns, or we may work through a fictional scenario with all the different organisations participating in their offices.

Sometimes we do a live exercise at a hospital or on a high street, simulating the scenario and testing the first response elements on the ground. Many people will have seen the chemical contamination exercises, with volunteers acting as if they’ve been contaminated and responders in their protective suits, looking like big, inflatable Michelin men.

Those exercises identify lessons that we feed back round the loop to develop another version of the plan, and we keep doing that. Emergency planning is very cyclical in that way.

But at some point do you have to say, “this is the plan for space weather” and move on to the next threat? Yes, no plan survives first contact with reality, but you get to a stage where it’s as good as it’s going to get without being activated—and then there’s probably something else which is more pressing and at a less-ready stage. But if we’ve not activated the space weather plan after a few years, we’ll go back and look at it again.

Space weather: how solar radiation can play havoc with the NHS

‘Space weather’ describes a series of phenomena originating from the sun, which can collide with the Earth’s ‘magnetosphere’ – the magnetic field that protects us from harmful radiation. Space weather phenomena include:

- solar flares: intense eruptions of electromagnetic radiation in the sun’s atmosphere, which can reach Earth in a few minutes

- solar energetic particles: accelerated particles, mostly protons, emitted by the sun, which can penetrate Earth’s planet’s magnetic field in about 15 minutes

- coronal mass ejection: a major release of plasma and its accompanying magnetic field from the sun’s corona, which can take up to four days to reach Earth

Day-to-day space weather causes such harmless phenomena as the Northern Lights (Aurora Borealis), but a severe event could lead to significant disruption, including:

- power outages

- loss of satellite communications

- radio and TV blackouts

- disruption to transport, retail, energy and communication services

- damage to phones and computer equipment

- increases in radiation doses, particularly in space and at high altitudes

Severe space weather isn’t the stuff of science fiction. In the 1859 ‘Carrington Event’ – the biggest recorded space weather incident to date – telegraph services were severely disrupted and the Northern Lights were seen as far south as Mexico.

Severe solar storms in 1921, 1960 and 1967 caused widespread disruption to radio transmissions and railway signalling systems. As recently as 2003, another solar storm knocked out GPS satellite systems for a day, causing cancellations and delays to flights in the UK and USA.

As well as the direct impact of power outages and disruption to computer systems, a severe space weather incident could have significant indirect effects on the NHS, including shortages of staff and supplies, disruption to ambulance services and an more patients needing emergency treatment.

Do all NHS organisations have to develop their own plans for dealing with each emergency?

Yes, and organisations are required to do live exercises and update their plans at regular intervals. But what they can realistically do depends on the scenario. With space weather, for GP’s it’s mainly about business continuity—what to do if they lose power or staff can’t get in—but it’s a different magnitude of problem if we lose power to a 4,000-bed hospital.

All trusts have an accountable emergency officer—someone at exec level with overall responsibility—but also at least one person doing day-to-day emergency planning, training and so on. A GP practice probably won’t have someone dedicated to that. With ICSs, I think we can do some wider thinking about emergency planning in primary care, building on what we’ve seen in the Covid response—looking at how secondary care, local authorities and others can support primary care, and vice-versa, in periods of disruption and challenge.

Okay, can we talk about Covid?

Yes, but I might not be able to answer everything because of the inquiry that’s coming up.

I understand. What plans did you already have for a pandemic and how did you adapt them for Covid

Historically, we’ve planned for an influenza pandemic based on our experiences in 1918, 1957, 1968, and the swine flu pandemic in 2009. With that magic look back, you could say a pandemic caused by another disease wasn’t given enough prominence but that was really no different to what other countries were doing.

So we looked at existing plans—for a flu pandemic, for periods of winter surge, for high-consequence infectious diseases like Ebola—to see what we could rapidly adapt, tailor and use. Scientifically, it’s fascinating how much we’ve learned about this virus, but at the start, we had no idea what Covid was, how infectious it was, how it transmitted or any of those essential things.

We established a co-ordination centre and a dedicated team, recognising that it was going last much longer than a terror incident or flood. We needed dedicated communication systems, dedicated filing systems, a whole range of things to make the response run smoothly. For example, I used a generic mailbox, not my personal work email, so that if I got sick or died, someone else could immediately take over from me.

What lessons do you draw from the Covid response so far?

That there’s a real benefit to building good relationships in advance, so that when something happens, 90% of the time you know who you’re dealing with and you can hit the ground running.

A second lesson would be—and I’ve not quite finished working through this—that the response tended to work better when we said what needed doing and let people at local level work out the best way to do it. We need enough agility and flexibility in our plans so they work for people in slightly different scenarios.

And lessons for you personally?

To actually take a break and not keep going until I break myself. It was really hard to step away during the emergency response and not feel like you were letting people down. So we need to build that redundancy, in a positive way, into our planning, so staff don’t end up feeling like that and we don’t have potential single points of failure.

It sounds like a fascinating but nerve-wracking job. How did you get into this line of work?

I’m a biochemistry PhD by background. I worked in the Health Protection Agency until 2007, specialising in pandemic flu guidance. Then I moved to an operational role at the London Strategic Health Authority, translating policy into something usable for the NHS.

Is that a typical background for an emergency planner?

My team here in London have all got very different backgrounds. We’ve got people with clinical backgrounds, who might be emergency department nurses or paramedics, we’ve got people from police backgrounds, we’ve got people who’ve studied disaster risk management at university. Then you’ve got people like me, from an academic or public health background. We all think slightly differently, we have different experiences and that melting pot of ideas is really beneficial.

Can you give me an idea of what a typical day looks like?

There probably isn’t one, really, and that makes the job really interesting and positively challenging—but also frustrating at times. I quite like that uncertainty within some boundaries. When your pager goes off—yes, we still use pagers!—you never know what’s going to happen.

At the moment, we’re still having regular meetings on the Covid situation and the recovery, as well as looking at readiness for winter and having discussions on the ICS transition.

What part of the job do you enjoy the most – and what could you do without?

I enjoy the job most when I can see that it’s making a difference. We were involved in repatriating people from Afghanistan recently—quickly activating support to greet and assess people at port, triage, taking them to hotels and arranging ongoing support and so forth. Sometimes it can feel like you’re writing plans that don’t mean anything. But that felt meaningful.

Every year we offer an undergraduate student a placement to work in our team. Helping to grow this person into an emergency planner is one of the most fulfilling things I do. Of the four students who’ve completed their degrees, three are now emergency planners—two in the NHS, and one in a local authority.

Like everyone, the thing that’s most annoying is probably the forms and paperwork, and collecting data when you can’t see how it’s going to make any difference. EPRR’s full of counting, sometimes just for the sake of counting, it feels.

How do you cope with all these inherently stressful situations? Do you lie awake at night worrying about things like space weather?

They don’t necessarily keep me awake at night, but I’m a terrible person to watch a disaster movie with! I’m always saying, “Well, that wouldn’t happen, that’s not how the ambulance service would respond and that’s not what those people would be wearing.”

I think there’s a certain type of character that’s drawn to this role. It’s exciting, it’s challenging, it’s interesting, but at times it can be pretty horrific being conscious of all the things that might trigger a disaster.

But we have very good support networks and when something happens we’re very good at debriefing—both identifying lessons and sharing experiences and offloading. But there are times when it becomes overwhelming. When the clapping for carers first started, I remember heading home on the bus one night, and when I saw all the people out on the street, I burst into tears.

Finally, is there a particular threat that’s nagging away at the back of your mind, where you’re thinking, I’m not sure we’re across that yet?

For me concurrency is the big concern: what if we get three or four scenarios all at the same time? I’m eternally grateful that we didn’t have the events of the summer of 2017 in 2020. It would have been incredibly challenging, not just for the NHS, but for the whole resilience partnership.

Thank you so much for your time, it’s been absolutely fascinating. And thanks for everything you do for us.

You’re very welcome.

Risky business: what is an emergency?

The 2004 Civil Contingencies Act defines an emergency as “an event or situation that threatens serious damage” to human welfare, the environment or the security of the United Kingdom. Emergency planners in the NHS and other public services usually develop plans for the “risks” or “scenarios” outlined in the National Risk Register (NRR), which is compiled by the Cabinet Office and updated every two or three years.

The key risks identified in the 2020 NRR include:

- Environmental hazards

Floods; severe weather such as heavy snowfalls, prolonged heatwaves and droughts; severe space weather (see opposite); earthquakes, pollution; volcanic eruptions abroad that may affect the UK.- Health risks

Human pandemics like Covid-19 and non-seasonal flu; animal diseases which could spread to humans or cause serious damage to the economy or the natural environment; resistance to antibiotics and other drug treatments.- Major accidents

Widespread loss of electricity, gas or water supplies; failure of financial or telecommunications systems; major transport accidents; industrial accidents; major fires.- Societal risks

Widespread industrial action; riots and civil unrest; organised crime, drugs and firearms; people trafficking and modern slavery; bribery and corruption; child sexual abuse- Malicious attacks

Terrorist attacks on public locations, transport systems or key infrastructure; chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear attacks; cyber attacks; disinformation- Overseas risks

Conflict, violence, terrorism, major transport disruption or other incidents abroad affecting UK citizens or having a major impact on the UK.

Related News

-

Daniel Elkeles: “There’s a lot of green shoots here—the NHS is in a much better place”

As NHS Providers annual conference gets underway in Manchester, we speak to chief executive Daniel Elkeles about next year’s merger with the NHS Confederation and the future for NHS trusts in England. He tells Alison Moore that providers are “well placed” to deliver the Ten-Year Plan—but warns an unhappy workforce and a lack of investment could throw big spanners in the works.

-

Angela Hillery: “Nobody can do this on their own”

Angela Hillery, chief executive of community trusts in Northamptonshire and Leicestershire, is one of England most influential NHS leaders and a pioneer of collaborative working. She talks to Craig Ryan about why integrating services offers the best chance of overcoming a hostile environment and turning the NHS around.

-

We’ve given NHS management a home – we care for it and campaign for it

MiP is 20 years old this summer and its chief executive, Jon Restell, has been there since the beginning. He reflects on the union’s past, present and future in conversation with Healthcare Manager editor Craig Ryan.