STPs: what’s in store for NHS managers?

Sustainability and Transformation Plans may save the NHS or drag it further into the mire. But staff and patients have been shut out of the conversation so far.

STPs are the flipside of the Five Year Forward View. The 5YFV’s broad vision for the NHS was breezily optimistic, but STPs are – or will be – all about the grinding detail of realising it. In these 44 hastily cobbled-together “footprints” the stark reality of what £22bn in efficiency savings really means for the NHS will play itself out.

As the King’s Fund recently observed, STPs started out as being all about new care models, integration and public health but “the emphasis from national NHS bodies has shifted over time to focus more heavily on how STPs can bring the NHS into financial balance (quickly).”

Most STPs have now found their way into the public domain one way or another. But it’s as clear as mud what they mean for people working for the NHS. Most of the STPs I’ve read have little to say about the impact on the NHS workforce, and engagement with staff and their trade unions – as with patients and the public – seems to have been minimal at best.

Superficial, high-level stuff

Superficial, high-level stuff

“You’re looking at extremely superficial, strategic and high-level stuff at the moment, there’s no nitty-gritty about what it’s going to mean for the people of this area and staff who work for the NHS,” says Steve Smith, MiP’s national officer for the South Central region.

He says discussions at regional level on the STPs in Berkshire, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire (known as “BOB”) and Solent have not got beyond talking about eye-watering deficits and “high level aspirations” like giving pharmacists the power to dispense. “Obviously, there must be discussions going on about what that means for staffing levels, service changes and hospital closures, but they’ve not been shared with either the staff representatives or the public,” says Smith.

A similar story emerges almost everywhere – with the shining exception of Suffolk and North East Essex, a relatively small STP centred on Ipswich and Colchester. Here, following talks with unions, Ed Garrett, chief executive of two of the three CCGs within the footprint, has gave an undertaking to staff that there will be no compulsory redundancies as a result of the STP.

“This should be seen as a standard setter,” says George Shepherd, MiP national officer for the East of England, who played a leading role in the talks. Garrett’s promise is rooted in a history of constructive engagement in Suffolk, Shepherd explains. “The partnership agreement we signed two years ago means we’ve built a very strong relationship with the CCGs, and this assurance comes from the involvement of the staff side at an early stage in the STP process.”

No redeployment process

MiP chief executive Jon Restell explains that employers only have a legal duty to look for suitable alternative employment – as an alternative to redundancy – within the same organisation, even when job losses are a result of a multi-employer STP process. “If people fall out of the tree, we need some sort of outside-the-employer intervention to match them up with suitable jobs elsewhere within the STP footprint or even the wider region,” he says.

Shepherd has called on employers to put a block on external recruitment and “ring fence” new jobs to maximise redeployment opportunities for existing staff across the region.

“If there are jobs available and there are people at risk of redundancy, they should be given the first chance to apply for them,” he explains. “That seems a common sense approach, even if they’re in a different STP. HR leads at regional level need to be talking to each other about this.”

Finding alternative jobs is particularly tough for very senior managers, says Corrado Valle, MiP national officer for

the North West. In Central Manchester, three CCGs are being merged into a single commissioning body, potentially displacing several executive directors. “Quite simply, the higher up the management chain you are, the harder it is to be redeployed,” he explains.

Back office mergers

Across the North West, details remain sketchy, but the direction of travel is clear, says Valle. “Back-office mergers, reducing duplication to zero – the name of the game is to save as much money as possible.” Cheshire and Merseyside STP is typical, with plans to merge procurement, recruitment, occupational health and training. “This is happening across CCGs but providers are starting to have similar conversations,” he adds.

NHS England and NHS Improvement have put great pressure on CCGs and providers to merge back office services. At the end of November, four STPs – North West London, Kent, Essex and Greater Manchester were chosen as “pathfinder” STPs – charged with developing blueprints for other STPs to follow. All four had included back office mergers in their STP submissions, but only Essex quantified the savings it expects to make – £10.5m a year, but only if upfront capital funding is available.

Specific plans for merging clinical services – and especially for closing hospitals – were largely kept out of the initial plans submitted to NHS England in October. Health minister Philip Dunne told MiP’s conference in November to expect “significant political resistance” to the next phase of STPs as the pattern of reconfigurations becomes clear.

“I understand why the powers that be are anxious to avoid those conversations, because that’s when communities get defensive,” says Smith. “At the moment, it’s all just tootling along under the surface like a torpedo and most people just don’t know anything about it.”

Hospital closures

Hospital closures

We do know that one of the five big acute hospitals in South West London will close. With St George’s deemed safe, the fate of the hospitals in Croydon, Epsom, St Helier and Kingston hangs in the balance.

Jo Spear, MiP national officer for the South East, says it’s very hard to see redundancies being avoided in the bigger London STPs, but no one knows where the axe will fall. “There is movement but it’s very slow. And it’s very slow because NHS England put the kibosh on anything that looks like detail,” she says.

“Sutton Council published the STP against NHS England advice, raising concerns about its content and the way it’s being conducted,” she adds. “Most of the information has been coming from councils, not NHS organisations. That speaks volumes, doesn’t it?”

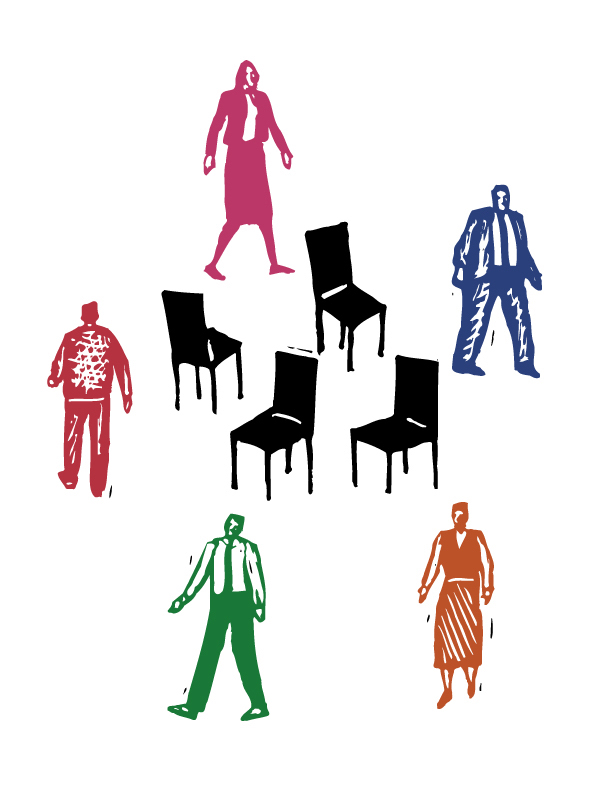

Musical chairs

In this game of musical chairs, when the music stops even those managers who are sitting down may find themselves in different seats with a different employer’s name on their payslip. And finding a suitable perch will be made even more difficult by the lack of a national or even regional framework for redeploying people or moving them between the NHS and local government.

“Organisations’ practice in grading jobs under AfC varies enormously,” Restell explains. “We’re finding new jobs are being graded poorly, and new structures are being presented without job descriptions or grades. People are asked to make decisions about moving with very little information. And this is going to be happening all over the country at the same time.”

Shepherd says STPs require a common approach to job evaluation and consistency checking. “Even if there’s no redundancies, they’ve still got to make savings and we’ve seen jobs being downgraded even when the core goals and responsibilities are the same.”

With the integration of health and social care, Spear warns that STPs risk repeating the chaotic transfer of public health staff to local authorities seen during the Lansley reforms.

“The MoUs for public health staff were largely set aside,” she says. “The workforce lead for one of my public health areas said she’d never heard of it, she’d never seen it, we didn’t sign it, so it doesn’t apply to us. But it does apply to them. The process was supposed to be overseen by Public Health England, but that didn’t happen in practice.”

Worthless promises

Of course, patient care will inevitably suffer as skilled and experienced managers leave and those that remain lose their focus on the job in hand. “Even people who understand what’s going on are overwhelmed by the speed of the change,” says Spear. “And the concern I’ve got is that we will lose organisational memory and the ability to handle skilfully these and future changes.”

Valle warns that bigger organisations, thinly staffed with managers, may become more remote from frontline services – the opposite of the government’s intentions. “On the one hand they may be lean and efficient organisations, but on the other, how manageable will managers’ workloads be? If they’re enormous, you tend to end up far removed from what’s happening on the ground.”

He says the “the vast majority” of managers he speaks to “see the logic of trying to unify the system and address the particular needs of the communities they serve. Potentially, the single hospital in Manchester will be a good thing. But the implementation is chaotic and piecemeal, and being done without realising what happens in one area has an effect on another.”

Complex workaround

It’s often claimed that STPs have brought people together across health and social care who have never met before. But, ironically, the 44 STPs themselves seem to have retreated into silos, with little sign of regional or national co-ordination – over redeployment or anything else.

“It’s a bit like the first inception of CCGs,” says Valle. “Because they were a legal entity in their own right, they decided they didn’t need to talk to their neighbours. They commissioned completely different stuff even though they were next door to each other.”

MiP has joined other health unions, led by UNISON, in calling for a slowdown in the pace of change to allow for proper consultation with patients and staff. Writing to NHS chief executive Simon Stevens, UNISON head of health Christine McAnea proposed a “national compact”, to be mirrored at regional and local level, on the workforce consequences of STPs – including how redundancies and redeployments will be handled.

Related News

-

NHS job cuts: you’ll never walk alone

As the NHS redundancies in England loom, Rhys McKenzie explains how MiP will back you, and how members supporting each other and acting collectively is the best way to navigate this difficult process.

-

What now? Seven expert takes on the Ten-Year Plan

The government’s Ten-Year Plan for the NHS in England has met with enthusiasm and exasperation in equal measure. We asked seven healthcare experts to give us their considered view on one aspect that interests, excites or annoys them.

-

NHS job cuts: what are your options?

When politicians start reforming the NHS, there is only one certainty: some people will lose their jobs. But what options might be on the table and how does redundancy work? Corrado Valle explains.