NHS shared services: lessons from the public sector

What are the lessons for the NHS from the troubled history of shared services in the public sector?

Last June Jim Mackey, the chief executive of NHS Improvement (NHSI), asked Sustainability and Transformation

If higher-spending NHS bodies reduced their back office costs to the median for their organisation type, NHSI believes system-wide costs would fall by over £480m – although it acknowledges that many of the potential savings lie in the tricky areas of IT and governance and risk, which contribute 33% and 25% respectively to its estimates.

Jeremy Marlow, NHSI’s executive director of operational productivity, tells Healthcare Manager the new figures “shine a light to show [NHS trusts] where money can be saved”. Following “a big data trawl, function by function and trust by trust”, Marlow’s team are returning benchmarked spending figures to managers across the NHS that show “big variations” in back office costs. “The hard work begins now,” he says. “What’s the change needed to release that?”

Four pathfinders

That hard work is beginning in four pathfinder STPs: North West London, Greater Manchester, Mid and South Essex, and Kent and Medway. “We wanted a spread across the country, and different levels of maturity on where they were with their discussions. They’re all coming at it from different angles”, says Marlow. The five pathfinders are examining various options, from creating central teams within one trust to outsourcing services to a private company.

It’s an ambitious plan, and one demanding major organisational and process changes across the NHS. To share back office services, NHS bodies must first unify their management information formats and processes. “You’ve got a bunch of providers in each patch using different systems for finance, HR and other services,” Marlow explains. “The first thing to do, over the next six months, is move to common management information systems; the next stage is to move to one provider; and the stage after that might be to put it out to the market and see who can do it better.” Ultimately, NHSI wants to use economies of scale and technologies such as cloud computing, automation, artificial intelligence and analytics to both improve service quality and drive down costs – returning savings for use on the NHS frontline.

Troubled history

Many NHS managers, though, are wary of NHSI’s plans because shared services have a troubled history in the public sector. An NHS Wales scheme has made fair progress. But last month it emerged that NHS Shared Business Services (SBS) – a joint venture between the Department of Health (DH) and Sopra Steria – left 500,000 items of medical correspondence, including test results, unread in a warehouse over a five-year period. And Capita’s 2015 contract to provide primary care support experienced what the BMA called “multiple serious failings”; last autumn, MPs secured a Commons debate on the issue and Capita apologised “for the level and varied quality of service we have provided”.

Shared services present many risks and challenges. As organisations adopt common business processes, they lose the advantages of tailored systems built around their specific needs. And, once committed to a shared system, their freedom of manoeuvre is limited. Jon Restell, MiP’s chief executive, says managers will fear “losing sovereignty and control over a key business function”.

Finding the necessary management time and specialist skills will also be a concern: “It’s a huge piece of work to dump on a management team that are trying to do 101 other things,” says Restell, warning that it will require excellent change management and careful alignment with other reform programmes.

Then there’s managers’ and teams’ reluctance to transfer into outsourced providers: “Employees with values and commitment and decades of experience see their role as integral to the work of their organisations,” he says. “We’d want people to remain NHS employees. That allows people to go into change processes, in which they may lose their jobs, knowing that they won’t lose their values.” Given that many of the potential savings lie in offshoring work, the chances are that many jobs will not only leave the NHS, but also the UK.

Cabinet Office errors

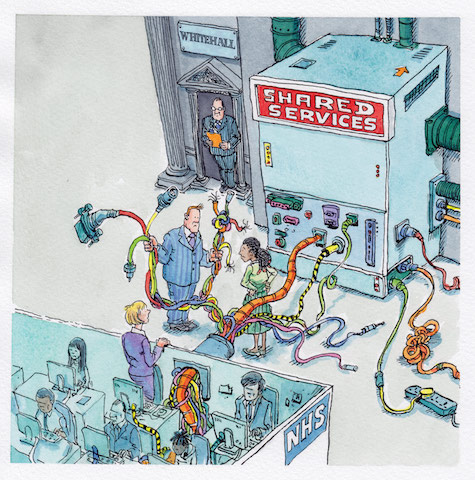

NHS managers familiar with the Cabinet Office’s longstanding efforts to share services between Whitehall departments will have another set of fears. Its 2012 Next Generation Shared Services strategy involved moving back office functions from almost all departments into one of two centres (although DH escaped the three-line whip, pleading that it already ran its own centre in the shape of NHS SBS). But the strategy quickly ran into trouble: in a highly critical 2016 report, Amyas Morse, head of the National Audit Office (NAO), said the Cabinet Office’s “failure to manage the risks around the move… means that the programme has not achieved the significant anticipated savings and benefits”.

The Cabinet Office made several serious errors, explains Paul Oliffe, the NAO director who led the report team. “There was no assessment of how far organisations would have to change their processes” to adopt common management systems. “This gap analysis is really important, and it was never done,” he says.

Once organisations have carefully examined the costs of rebuilding back office processes, they may find some of the theoretical savings are not cashable, warns NAO director of health value for money studies Robert White. For example, “some services are sitting in hospital estate that you can’t release to produce capital savings,” he says. “If I had a message to the system, I’d say: ‘debunk the myths, and identify the real savings’”.

The Cabinet Office also failed to give departments sufficient incentives to adopt common processes, says Oliffe. Participants received discounted services from day one – whether or not they’d made the leap to new management systems. Unsurprisingly, many departmental timetables then slipped, leaving suppliers unable to realise the savings built into their business plans. But the Cabinet Office refused to take the lead in corralling departments and, eventually, all the departments slated to join one of the new centres walked away. This type of reform needs clear central leadership, Oliffe insists, and system leaders “should speak with a single voice to prioritise, to performance manage, to think about key dependences in getting to an overall objective”.

NHS “beacons”

NHSI’s Marlow, a former senior civil servant, is all too familiar with the weaknesses of the Whitehall programme. “I was a customer involved in [the civil service project], and the learning for me was that you have to understand the processes and get the commitment and buy-in of organisations involved,” he says. “We think the [NHS] pathfinders get that, and they’ll be beacons to others about how to do it.”

Those pathfinders are, he argues, “advanced in working out where the commonalities are across their HR and finance functions, and what re-engineering can be done. That’s given them and me confidence that we can find those commonalities.” The pathfinders’ exploratory work should provide vital evidence on how and where real savings can be found, and help NHSI work out how best to help other STPs along the same road. “If we don’t manage this properly, we’ll lose people on the way,” says Marlow.

Talk to staff and unions

Marlow won’t make any commitments about keeping staff in the NHS. “It’s not in my gift to tell employers how to treat their employees,” he says. “What I would say is that managers should be perfectly transparent right from the beginning, and talk to staff and unions.”

However, he does promise that NHSI will ensure that NHS bodies “don’t have to do this from scratch: we can do some of the groundwork, and create some common frameworks.” To this end, he urges STPs to “share what they’re doing, so we don’t have to reinvent the wheel 44 times over”. STPs’ plans won’t need to be signed off by NHSI, but Marlow clearly intends to push organisations to participate and to maintain momentum.

“By the time we’re getting into Quarter 2 [of 2017-18], I need a lot more than the four pathfinders to start making progress – and I’m happy for the NHS to hear that loud and clear,” he says. “If I think this is right for a trust and they’re not interested, then we’ll have a view on that when we’re considering whether they’re using their resources correctly in the shared CQC inspection regime.”

Jon Restell warns that, before NHS bodies come under pressure to hit deadlines, they must be permitted to “come to credible, evidence-based, piloted solutions – and that may not deliver savings until the medium-to-long-term. If the programme is pushed in a year-by-year savings-based way, it won’t work: we’ll take out cost, but lots of it will fall over.” Staff engagement and empowerment will be crucial – back office services must not fall in quality – and whatever solutions are adopted, staff “must be valued and seen as part of the NHS team, as people who are essential to running NHS services,” he says.

Turning a corner

After years in the doldrums, the civil service scheme has now begun to pick up: the Ministry of Justice (MoJ), Defra and the Environment Agency have rejoined the programme, and Oliffe reckons system leaders have demonstrated that big public sector organisations can share back office services. The Whitehall scheme has “certainly stabilised, and is moving in the right direction,” he says.

The programme turned a corner, he adds, when the civil service’s cross-departmental professional networks began to take a lead, “taking it away from what it means for the MoJ or Defra, and saying instead ‘this is what the finance profession needs’”. For Oliffe, the fact that “they’ve got the professions lined up, working out what is needed in each field, is the biggest indicator that they’ll stop making the same mistakes”.

Nonetheless, civil service shared services are still far from successful, and enthusiasm less than universal: the DH failed to answer questions from Healthcare Manager over a period of five weeks, but it appears the department still doesn’t buy its own back office services from NHS SBS.

Let’s be realistic

Jon Restell sounds reassured that NHSI, which does use SBS, will take a sensible approach. “They’re not just saying, ‘That’s a saving, let’s take it out’,” he says. “They’re looking at the models, and testing them. I hope most of the models are NHS ones.”

“This will need proper time,” he adds. “Let’s be realistic about what people can manage; let’s prepare people for change, and introduce proper processes. We want something evidence-based, something that continues to offer good support to frontline services.”

Related News

-

NHS job cuts: you’ll never walk alone

As the NHS redundancies in England loom, Rhys McKenzie explains how MiP will back you, and how members supporting each other and acting collectively is the best way to navigate this difficult process.

-

What now? Seven expert takes on the Ten-Year Plan

The government’s Ten-Year Plan for the NHS in England has met with enthusiasm and exasperation in equal measure. We asked seven healthcare experts to give us their considered view on one aspect that interests, excites or annoys them.

-

NHS job cuts: what are your options?

When politicians start reforming the NHS, there is only one certainty: some people will lose their jobs. But what options might be on the table and how does redundancy work? Corrado Valle explains.