Turning the mirror inwards: why inclusion starts with self

Reflecting on our own assumptions and behaviour is the first step towards inclusive leadership. By putting ourselves in other people’s shoes and learning from conversations we can use the power we have to create more inclusive and productive workplaces, writes Ramima Khanam.

Just as plants need soil, water and sunlight, we human beings can only thrive if our behavioural needs are met. Over 65 years ago, the American psychologist William Schutz identified inclusion, control and affection as the three fundamental behavioural needs we all have, regardless of our position in society. The extent of our need varies but all three elements must be met for us to feel whole. Just like a plant, if our basic needs are not met, we’ll start to wither away.

I’m going to focus on inclusion, as it’s a cornerstone of organisational values and culture. Given that it’s the relatively simple act of including people and there’s lots of information available, why do so many people find inclusion difficult to put into practice?

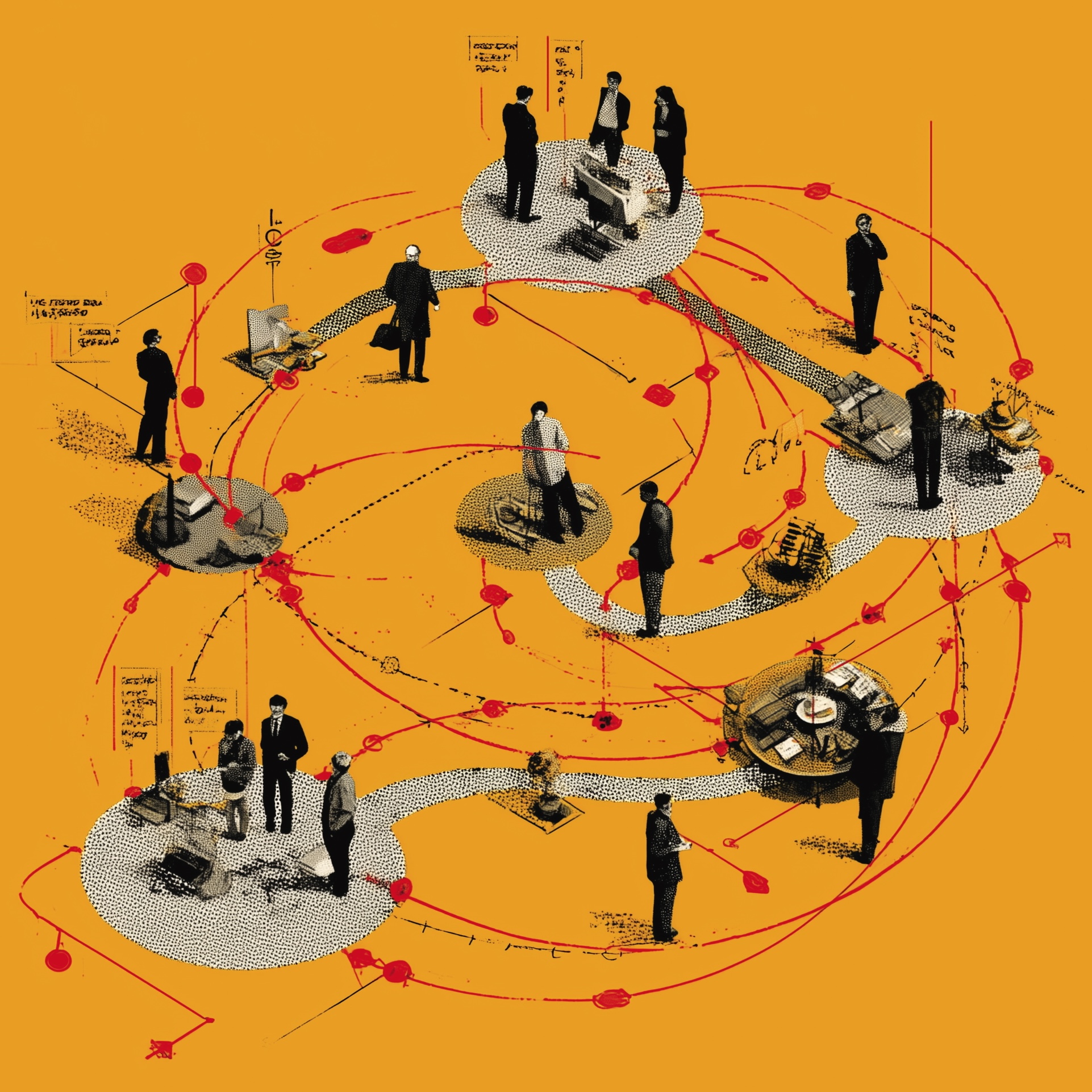

To answer this, I undertook a small-scale, action-based inquiry with a group of people representing a cross-section of English society. I called it ‘Acts of Inclusion’. My experiential model involved noticing, reflecting and acting — where safe to do so — while recognising that failure is important for growth and and continuous learning. We used philosopher Donald A Schön’s model of reflective practice, which emphasises reflection both during and after taking action (see mip.social/schon for a brief explanation). The strength of this study was that it humanised inclusion, something I found missing from a lot of the literature.

I’ve grouped my findings under six interconnected headings.

1. Inclusion is subjective

No matter how many policies or strategies are written, programmes developed or mandatory training sessions held, inclusion will always be subjective. We feel included or excluded. Inclusion doesn’t happen just because the idea has been planted. It’s a felt sense of belonging and individuality that is created by behaviours.

2. Inclusion depends on behaviours

Who and what we are exposed to — good or bad — nourishes our behavioural roots and becomes our mental model for responding in social environments. We seldom question this lived and imparted knowledge and consciously model other people’s behaviours, especially those who we hold in high esteem.

Our motivations also drive our behaviours. When we’re rewarded, through praise for example, we feel good and want to get that feeling again by repeating the same act. The reverse is also true. Our mental model is deeply ingrained and full of assumptions, which manifest themselves in how we interact and the language we choose to use. This affects our ability to treat people inclusively.

3. Assumptions drive our behaviours

Assumptions are fact-less, habitual thoughts that we believe to be true based on past experiences. They inform every decision we make and drive our behaviours. This is because we use mental shortcuts called ‘heuristics’ to help us navigate our experiences. These shortcuts are prone to cognitive biases and affect how we think and interact with people. Assumptions and biases fuel judgements that can turn into harmful exclusionary behaviours such as stereotyping and discrimination.

We all have the seeds of assumption within us and they grow the more we tend to them. So it’s important to challenge our own assumptions by consciously noticing them and how they affect our ability to see.

4. Seeing is selective

For many of us, seeing is an immediate sensory response to stimuli that trigger our brain. But research in perceptual psychology shows that our brain uses a filtering system to focus only on what it thinks is important based on our mental model.

This selectivity is further compounded by our wandering mind, with its uncontrollable and kaleidoscopic flows of thoughts and feelings. These are influenced by an invisible mental load we all carry but seldom share: maybe we didn’t sleep well, have financial or family worries, or have just had an argument, for example.

All these factors affect how we show up in social environments, and our ability to truly see, and be engaged and inclusive — as well as our interpretation of what inclusivity means. Subconsciously, we relinquish many of our choices by not fully paying attention. It’s easy to miss something you’re not looking for, don’t want to see or don’t think is important.

By slowing down our brain and tuning into our internal and external world, using our senses and paying attention, our eyes can see what’s really going on beneath the surface of our experiences and respond accordingly. But this requires power.

5. Power can be used to promote inclusion

Power resides everywhere. But while we sense it and feel its impact, other people around us are also experiencing the impact of the power we have.

Privilege is an embodied imbalance of power. We all have privilege to a greater or lesser extent. It’s what gives some people an advantage over others and that advantage is acutely felt by people who are not in the dominant group. With privilege can come ignorance, but allyship is when someone uses their privilege to create inclusive experiences. Being truly inclusive means relinquishing some power in order to influence change through leadership.

6. Leadership is a catalyst for change

We tend to underestimate the impact of our behaviours on people. The way we lead is influenced by our lived experiences. Good leadership plays a significant role in creating an inclusive culture because it’s a catalyst for change — allowing transformation to happen through transparent role-modelling, and by paying attention to the needs of others and responding in a inclusive way.

Good leaders treat everyone equally. They recognise that exclusive leadership stimulates resistance and damages people, while inclusive leadership gives people a greater sense of self. This requires self-awareness, integrity and humility, which creates psychological safety and trust. Paradoxically these qualities give leaders more power through better staff engagement, productivity and retention.

Reflecting on our own practice

While inclusion is a multi-factorial, subjective phenomena, we can all make a conscious choice to be inclusive based on how we would like to be treated ourselves. We’ve all been in situations in our lives where we felt left out, not listened to or heard, and we can recall how it made us feel.

We can also think of times when we acted like this towards others — even unintentionally — and know it had an impact on them. Because time is limited, we can all become exclusionary in our practice. So we need to make time to consider the needs of the people around us.

The fact that you feel included, doesn’t mean everyone does. We need to put ourselves in other people’s shoes, because inclusion is fuelled by empathy — having common feeling with other people and wanting to connect with them. But first, we need to connect with our own sense of curiosity and the starting point is noticing: what is our reaction to this situation? What feelings do we experience? What questions does it raise for us?

To answer these questions, we need to do what the systems thinker Peter M Senge – who introduced the concept of ‘the learning organisation’ — describes as “turning the mirror inward” to reveal our mental model. As it’s easier to spot assumptions in other people than in ourselves, this can sometimes be uncomfortable. But by reflecting on our actions and having “learningful conversations”, we can open new perspectives and gain richer insights into ourselves and others. This will prompt growth and behavioural change, improving our ability to choose adaptive responses that create a more inclusive environment. This requires both power and leadership.

Practicing inclusion will make it a reflex action, helping you to cultivate and nurture a culture where everyone can thrive, and no one withers away.

After all, inclusions is a behavioural need for all of us, and by meeting it we are raising the standards for everyone. Inclusion simply requires the intention to do it.

Inclusion starts with self!

- Ramima Khanam is professional relationship programme manager for NHS England.

Related News

-

NHS job cuts: you’ll never walk alone

As the NHS redundancies in England loom, Rhys McKenzie explains how MiP will back you, and how members supporting each other and acting collectively is the best way to navigate this difficult process.

-

What now? Seven expert takes on the Ten-Year Plan

The government’s Ten-Year Plan for the NHS in England has met with enthusiasm and exasperation in equal measure. We asked seven healthcare experts to give us their considered view on one aspect that interests, excites or annoys them.

-

NHS job cuts: what are your options?

When politicians start reforming the NHS, there is only one certainty: some people will lose their jobs. But what options might be on the table and how does redundancy work? Corrado Valle explains.