Long Term Plan: more questions than answers

The NHS Long Term Plan is full of good intentions but fails to give health and care managers the tools they need to finish the job.

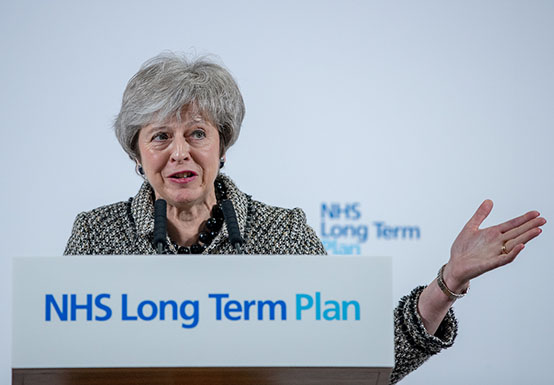

The NHS Long Term Plan for England (LTP), finally unveiled in January, contains much for NHS managers to welcome: commitments to improve care in key areas, including cancer, maternity services and mental health; proposals to accelerate the integration of health and social care services; moves to encourage collaboration rather than competition between NHS organisations; a renewed focus on prevention and public health; and the promise of more investment in new technology and community services.

But the plan appears to dodge completely the difficult issues that need to be resolved if these good intentions are to become reality. The social care green paper, which was supposed to be published “in tandem” with the LTP, has not appeared, while the unfininished NHS workforce strategy has now been absorbed into the LTP process. And it remains unexplained how the ambitious programme of improvements set out in the LTP can be realised when almost all NHS experts agree that £20bn of additional funding announced last summer is sufficient only to maintain current levels of service. Without these crucial elements, the plan ends up offering more questions than answers.

Workforce: a national emergency

The failure to offer solutions to the NHS workforce shortage is particularly disappointing, as this problem has been with us for years. A staggering 108,000 NHS posts are currently vacant. There is a shortage of 42,000 nurses (11.8% of posts) and 11,500 doctors (9.3% of posts). The nursing shortage is so dire that, in September, Siva Anandaciva, chief analyst at the King’s Fund, said staff shortages were becoming a “national emergency”.

But shortages among top managerial staff are almost as acute. Health secretary Matt Hancock admitted as much when he told the King’s Fund last year that “we don’t have enough leaders”. Nearly one in ten chief executive positions in the NHS aren’t permanently filled – right now, there are 20 organisations without a chief executive and 30 without a chief operating officer.

“Whether the plan can be delivered relies critically on tackling workforce shortages,” says Richard Murray, chief executive of the King’s Fund. “Commitments to increase international recruitment depend on decisions about immigration policy and we will need to wait for solutions until a new workforce plan is published later this year.”

The plan also contains little on two issues identified as priorities by Matt Hancock himself: staff training and diversity. In terms of gender and black and minority ethnic (BME) representation, the NHS is woefully behind where it ought to be. As Hancock has observed, 40% of hospital doctors and 20% of nurses are from a BME background, but BME representation on trust boards is only 7%. Women make up over 75% of the NHS workforce but only 40% of board members. The NHS would need 500 more women on boards to make them gender balanced.

Hancock has praised some of the existing training schemes for managers, including the new Clinical Executive Fast Track scheme, and has promised to expand the NHS Graduate Management Training Scheme and the role of the Leadership Academy, but says more and better management training is needed. MiP would particularly welcome more training – especially for newly-promoted managers or those taking on increased responsibilities – but has warned that training alone cannot solve workforce issues facing the NHS.

Regulating managers

But the LTP has little to say on management training or careers, beyond a vague promise to examine the “potential benefits and operation” of a professional registration scheme for “senior NHS leaders”. The plan suggests formal regulation of NHS managers could operate on the same basis as for other NHS professionals, such as doctors and nurses, but is silent on the question of whether managers could be ‘struck off’. It does refer to the review of the Fit and Proper Person test by Tom Kark QC, which is looking at the specific issue of professional sanctions for managers, but as that review also remains unpublished, the direction of travel on professional regulation remains unclear.

The plan also outlines proposals to introduce Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) across England by 2021, with a single CCG covering each area. But without new legislation, it’s unclear how ICSs will operate and MiP is concerned about the risk of competing regulations and confusion over which duties should be carried out by which body.

Social care black hole

But it is the further delay in the social care green paper which leaves the biggest hole in the Long Term Plan. The wait has been so long that in July last year the Local Government Association published its own green paper, recommending that the government “inject genuinely new national investment” to close the core social care funding gap – set to rise to £3.6 billion by 2024-25. It called on ministers to “make the case for national tax rises or other sustainable, long-term solutions and consult on clear propositions which explain the various options for how sufficient funding for social care and support could be raised nationally.”

When MiP recently surveyed our members, we found they identified social care as the highest priority for additional funding (followed by mental health services). There is clear anxiety in the healthcare sector about the impact of social care under-funding on the NHS, but it seems unlikely that proposals involving long-term taxation or other forms of funding will be seriously taken up in the green paper, when it appears, or the subsequent white paper which should follow the consultation period. As there have been twelve green papers on social care funding since 1998, is there any reason to think the next one will be the light at the end of the tunnel?

Sticking plaster

The failure to tackle the social care issue, and the continuing cuts to the public health budgets of local councils, also undermine the LTP’s goals of integrating health and care and shifting the focus of health services towards prevention.

“Wider political decisions outside the control of the NHS will also impact on its ability to deliver,” says Health Foundation chief executive Jennifer Dixon. “Without a solution to the growing crisis in social care, people will continue to suffer, and more pressure will be piled on the NHS. Without additional funding for public health, which runs services that are essential for keeping people healthy and reducing health inequalities, NHS plans in these areas risk stalling.”

It’s unclear why the government has chosen to bring forward a Long Term Plan which does not address workforce pressures, public health funding or the future of social care in the UK. The result is neither long-term nor properly a plan – rather a sticking plaster which wills the ends without providing the means to deliver them. Although there is much to welcome in the document, MiP will continue to campaign for a coherent workforce strategy for the NHS, and a credible and stable funding framework for both health and social care.

Mercedes Broadbent is communications officer for Managers in Partnership.

Related News

-

Strange ways, here we come

Creating a ‘neighbourhood NHS’ will demand a different mindset, unfamiliar ways of working and difficult decisions on finances and staffing. Middle managers as well as senior leaders will play a big part in making it happen, writes Nigel Edwards.

-

Labour’s reforms: a mixed bag for managers

Ahead of the ten-year plan, Wes Streeting and NHS leaders have been sketching out some ideas for NHS reform. Jon Restell and Rhys McKenzie explain what these initial proposals could mean for managers.

-

Jon Restell’s Leading Edge | Giving managers legitimacy is the key to making reform work

The false trade off between the frontline and everybody else has become a deep-seated belief in a two-tier workforce. The health secretary needs to unite all NHS staff and give managers permission, encouragement and the tools they need to get his reforms off the ground.