It ain’t what you do, it’s the way

that you do it

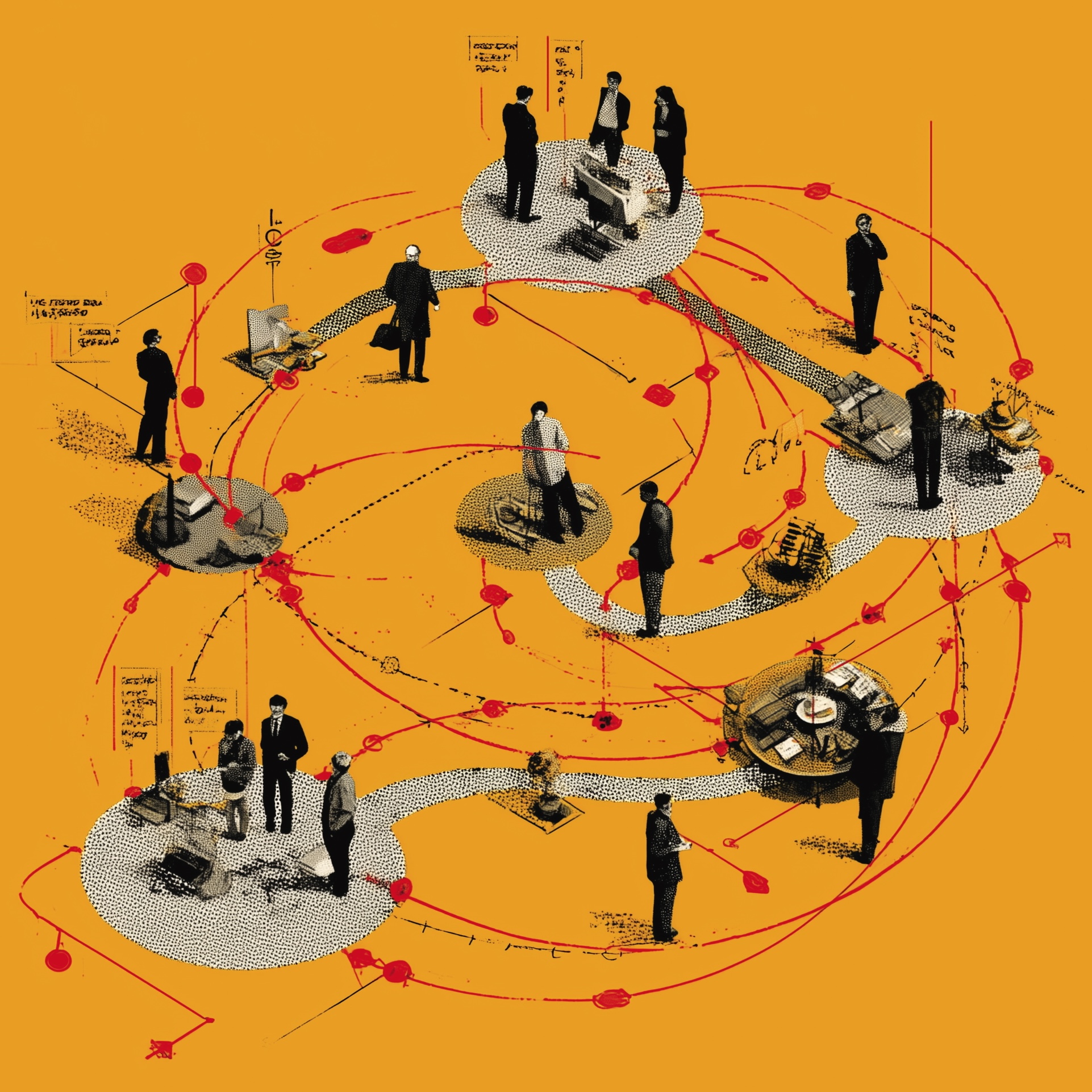

The government’s upcoming ten year plan will try yet again to shift the NHS towards community, digital and prevention. The big question is how. Try honesty, patience, focusing on what matters and empowering staff and local managers – that’s what gets results, writes Craig Ryan.

Here we go again. Another big NHS reform is just around the corner. Following Lord Darzi’s hard-hitting “diagnosis”, the treatment comes in May with the government’s ten year plan — “the biggest re-imagining of the NHS since it was founded in 1948”, according to Kier Starmer. No pressure, then, on the small team of officials drafted into the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) to write the damn thing.

Thanks to Darzi and the drip-feed of ministerial statements since, we know the plan will be built around the so-called ‘triple shift’: moving effort and resources from treatment to prevention, from analogue to digital, and from hospitals to community and primary care services. That’s nothing new — these shifts have been talked about for decades. The imaginative bit will be devising a plan that can be effectively implemented and delivered. The track record on this is patchy to say the least.

We’re already halfway through a ten year plan, which began in 2019, subsuming the (unfinished) ‘Five Year Forward View’, which in turn had started unpicking the chaotic Lansley reforms of 2013. Further back, Frank Dobson’s 1998 modernisation plan was upended within three years by Alan Milburn, who introduced foundation trusts and more competition. Funnily enough, Milburn’s blueprint was called the ‘NHS Ten Year Plan’.

So we’ve been round these houses before and we’re still only talking about starting that triple shift. What needs to be different this time?

Achilles heel

“The first thing is you have to be absolutely honest with the public that this involves trade offs,” says Siva Anandaciva, chief policy analyst at the King’s Fund and a former DHSC official. “Investing in the community and prevention might mean we have to wait a little longer for hospital care or even get poorer quality hospital care.”

Then you need time. We’ve seen how previous long-term NHS plans run out of steam: “the money goes away, the acronyms change, the focus shifts to something else,” Anandaciva says. “I was a big fan of the Five Year Forward View… but we just didn’t let it stick. So let’s pick something and stick with it for five or ten years.” The third key element, he says, is to “focus on implementation and do it well”.

Delivery and implementation is usually the “Achilles heel” of NHS reforms, says Sir Chris Ham, emeritus professor of health policy and management at Birmingham University. Ham was part of the team that produced Milburn’s plan in 2000 — widely seen as more successful than your average NHS reform.

“Much more thought needs to be given to how change and improvement are going to happen,” he explains. “Who are the leaders and what are the mechanisms? Nobody will really scream about the three shifts, but what do they mean in practice? You need to be very specific about how you’re going to bring those shifts about.”

He sees “a real risk” of conflict between action to tackle the immediate crisis and longer-term ambitions for reform. “Quite rightly, there will be pressure on the government to show it’s making a difference quickly—they can’t afford to wait six months—but that’s not what a ten year plan can realistically do,” he says. Promises of a “blitz” on waiting lists and waiting times through extra cash for hospitals and using more private capacity are hard to square “with a shift to putting more emphasis on primary care and community services,” he says.

There’s a danger, Ham warns, that ministers will reach for what they know and “we’ll end up with another very centralised, very-top down approach, very much based on targets. And I don’t think that’s the right way to go about it.”

Instead, ministers should think about “how to make hundreds if not thousands of small changes and improvements,” he says. “We’ve never been very good at linking up challenges with solutions, so this is an opportunity to draw on the expertise that already exists in the NHS and the energies of 1.4 million staff. That needs to be at the heart of the plan.”

Nirvana never comes

Some experts, Anandaciva included, are sceptical about the traditional approach to NHS reform: tackling the immediate crisis with emergency cash before the transformation kicks in. “The stabilise-to-transform narrative just leaves you waiting for a nirvana that never comes,” he says. “I struggle to see how you can flip the health service on its head and still meet all these constitutional targets. I think something’s got to give.”

That means recognising both the limitations of targets themselves and that we may be targeting the wrong things, he explains. “We could focus on a smaller range of targets or change what good looks like… because how long you wait for care is not all that matters. Nothing magical happens to you after four hours in an A&E department.”

Measuring people’s actual health outcomes rather than hospital activity would “cover more of the care pathway” and but raises tricky issues with accountability, Anandaciva explains. He recalls a recent meeting, where some ambulance service directors indicated they would be willing to take responsibility for an outcome target—such as survival to discharge rates for heart attack patients—despite not controlling the whole care pathway. “One said, ‘This is what matters. So, I’ll do my bit and make sure the rest of the pathway does its bit.’ At least that way we’d be measuring the right things,” says Anandaciva.

Forces for change

For change like that, you need heavyweight political cover. It would give him “more belief and more confidence,” says Ham, if Starmer, Rachel Reeves and Wes Streeting could “show the same joint commitment to reform and investment and, crucially, to seeing it through in the long term,” that Tony Blair, Gordon Brown and Milburn did 25 years ago.

The idea that politics can be taken out of major NHS reform is “both unrealistic and the wrong way of looking at it”, Anandaciva says. “A politician’s focus can be an incredible lubricant and force for change.” It may be significant that, unlike the last round of reforms, the ten year plan is being driven by DHSC rather than NHS England. It may also be significant that Milburn is advising Streeting on the plan.

But the NHS is under much greater financial pressure today than in 2000, when, Ham says, extra funding “was never in question”. Anandaciva doubts that Reeves’s October Budget stumped up enough cash to recover all the NHS performance targets and deliver the transformational changes the government expects. This leaves ministers with an ugly choice between another “massive cash injection” further down the line, or “a very different dialogue… about how we can spend the existing money differently,” he says.

But investing in prevention and community services, even at the expense of activity targets, “may not be as [politically] risky as we’ve been framing it,” Anandaciva adds, because we may be at the limit of what can be achieved by pouring in more money. “Yes, hospitals may be doing 25,000 more hip operations, but you’re still waiting five months for a referral,” he says. “People’s lived experience of the NHS won’t feel very different.”

As the huge response to the government’s consultation exercise on the ten year plan—70,000 responses in the first week—shows, there’s no shortage of ideas about how to reform the NHS, And the mixed and sometimes contradictory messages coming from ministers, the Darzi report and NHS England about ICS powers, managers, league tables, incentives and targets suggests the government doesn’t yet know it’s own mind.

Perhaps spare a thought for Anandaciva’s old boss from the King’s Fund, Sally Warren, who now leads the team developing the ten year plan. This shows how hard government can be: the issues are complex, the trade-offs are difficult, there’s no money and the cost of failure is very high. “I’m glad she’s doing it, but I really don’t envy her at all,” Anandaciva says. //

- What do you think should be in the ten year plan? Tell the government what you think at: change.nhs.uk

Related Stories

-

NHS job cuts: you’ll never walk alone

As the NHS redundancies in England loom, Rhys McKenzie explains how MiP will back you, and how members supporting each other and acting collectively is the best way to navigate this difficult process.

-

What now? Seven expert takes on the Ten-Year Plan

The government’s Ten-Year Plan for the NHS in England has met with enthusiasm and exasperation in equal measure. We asked seven healthcare experts to give us their considered view on one aspect that interests, excites or annoys them.

-

NHS job cuts: what are your options?

When politicians start reforming the NHS, there is only one certainty: some people will lose their jobs. But what options might be on the table and how does redundancy work? Corrado Valle explains.

Latest News

-

Government proposal for sub-inflation pay rise “not good enough”, says MiP

Pay rises for most NHS staff should be restricted to an “affordable” 2.5% next year to deliver improvements to NHS services and avoid “difficult” trade-offs, the UK government has said.

-

Unions refuse to back “grossly unfair” voluntary exit scheme for ICB and NHS England staff

NHS trade unions, including MiP, have refused to endorse NHS England’s national voluntary redundancy (VR) scheme, describing some aspects of the scheme as “grossly unfair” and warning of “potentially serious” tax implications.

-

Urgent action needed retain and recruit senior leaders, says MiP

NHS leaders are experiencing more work-related stress and lower morale, with the government’s sweeping reforms of the NHS in England a major factor, according to a new MiP survey.