Health and care integration: lessons from Scotland and Wales

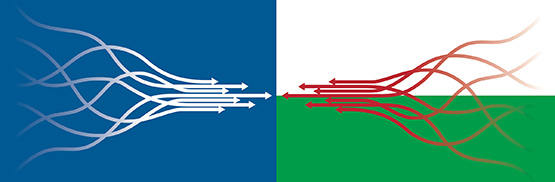

With the English NHS in a hurry to integrate health and social care, we examine the lessons from the well-established partnerships in Scotland and Wales.

The NHS in England is at last developing a more integrated and collaborative approach to health and social care, through initiatives such as integrated care systems and the Primary Care Home model. But while collaborative working remains the holy grail in much of England, Scotland and Wales have taken advantage of devolution to develop sophisticated approaches to integration that leave their larger neighbour in the shade. For England, its neighbours’ advances offer the chance to learn from their experiences and avoid some of the pitfalls.

The first lesson is the need to be realistic about the timescale: both Scotland and Wales took a considerable time to develop their approaches even once the political commitment to integration was there. In contrast to the hurried development of plans in England, Scotland’s commitment to integrated services dates back to the 1999 devolution settlement, explains Alex Baylis, assistant director of policy at the King’s Fund. Backed by long-term commitment from politicians – first minister Nicola Sturgeon has said she wants her legacy to be the quality of relationships between the people and public sector organisations – Scotland has been able to develop clarity on its values and take the time to design services with the public.

Scotland’s health bodies and single-tier councils are more coterminous than their counterparts in England, which may make it easier to draw in housing and leisure services, both of which can have a significant impact on the long-term health of the population. Many English ICS areas and even some CCGs have to deal with several top tier authorities, which may not make integration impossible but certainly adds an extra level of complexity.

Developing relationships

In both Scotland and Wales, the infrastructure behind integration has a legislative basis – in stark contrast to England, where integration initiatives are still tiptoeing around seemingly immovable legal restrictions. While no one thinks legislation is the answer to integration, it does give a framework within which relationships can develop.

“Trust, shared purposes, shared objectives, and a common understanding” are all important in health and care relationships, says Professor Mark Llewellyn, director of the Welsh Institute for Health and Social Care at the University of South Wales. The relative stability of Welsh NHS structures over the last decade has allowed collaborative relationships to flourish, he explains, while the abolition of the purchaser/provider split in 2009 means Welsh managers are not having to unlearn ingrained competitive behaviours: collaboration is now in the DNA of NHS managers in Wales.

And that collaboration has deepened since the setting up in 2016 of regional partnership boards, which aim to secure partnership working between local authorities and health boards. These often work very closely with charities and community organisations, with some chairs coming from the not-for-profit sector.

Llewellyn sees the regional partnership boards as having a potentially powerful role in deciding spending priorities and, while originally they were primarily concerned with health and social care, some boards have started taking a wider view – for example, by looking at the role of housing in promoting health and social wellbeing.

Health and care in Scotland

- 14 Scottish health boards plan, commission and deliver local health services, while a number of “special” boards provide national services.

- Legislation in 2014 led to the setting up of 31 integration authorities across Scotland, all but one of which are Integrated Joint Boards (IJBs) working across health and social care.

- IJBs have representatives from both the NHS and local authorities, and can be unwieldy in size – not all members can vote.

- Staff delivering frontline services generally remain with their old employers.

Opening up structures

MiP chair Sam Crane – who spent many years working in the Welsh NHS – says the Welsh approach to local integration “is all about collaborative transformation and new ways of working”. Key to this at local level are the Neighbourhood Care Networks, which build on the GP clusters seen in England by pulling in a wide range of local services, including district nurses, health visitors, dentists, optometrists and pharmacists, as well as social care services and housing associations. The networks help to plan local services with GPs, look at public health issues like smoking cessation, and have a remit to “sweat” local assets and funding.

It’s a highly inclusive model which contrasts to the approach in England, where CCGs and primary care networks remain dominated by GPs and managers from the existing NHS structure. Likewise, bodies which are meant to drive integration in England, such as STPs, have been slow to include lay members – and in many cases have had up-and-down relationships with local councils.

“England still has a long way to go”, Crane suggests, in harnessing some of the transformational opportunities at local level – especially those involving organisations outside the existing NHS system – and in enabling networks to work on their own local priorities as well as national themes and targets. “I think England is about five years behind in terms of the structure and collaboration,” she says.

In Scotland, the relatively new joint boards for each area – effectively single commissioners for health and care services – have developed new models of care and taken control of significant budgets, allowing them to shift resources around the system – a freedom often used to move funds towards community-based services.

Positive outcomes

Given the different geographical, public health and political challenges facing each country, it’s very difficult to assess the performance of the different models of integration across the UK. But the King’s Fund’s Alex Baylis certainly sees some positive outcomes in Scotland. “In general, Scotland has improved resilience, leading to fewer admissions, delays in discharge and crises for patients needing urgent care in winter – we found this was pretty much across the board the winter before last when we did our research,” he says. “More specifically, we found Glasgow was not only reducing hospital admissions but also reducing commissioned care home places, which appeared to be because their home care was so effective.”

But Baylis also points to examples of initiatives in England which are being quickly scaled up – such as the care home vanguard in Fylde, Lancashire – and raises the possibility that the environment south of the border may be more conducive to rapid change. “In general, some Scots look on with a bit of envy – although they should be careful what they wish for – at the way NHS England has created a burning platform and a sense of urgency, leading to more consensus and a faster pace of change,” he says.

In Wales, Crane believes the new collaborative structures have improved the way people and NHS organisations work together – and sees parallels with the new structures emerging in Greater Manchester. “But in Wales, everyone is part of the same organisation which does makes things easier,” she says.

Llewellyn agrees there is evidence that Welsh patients have benefited from more seamless care but warns against simplistically attributing outcome improvements to system change: “These benefits may have happened anyway”, he points out.

A key role for managers

Service integration can place an additional burden on managers, who must take on extra responsibilities at the same time as learning new ways of working. In Scotland, the chief officers of Integrated Joint Boards (IJBs) are in a powerful position sitting between health and social services, but have enormous expectations placed on them which they may struggle to fulfil. At least, unlike their counterparts in England – where many STP or ICS leaders still have a “day job” running a trust or CCG – IJB chief officers can focus solely on driving forward integration.

Claire Pullar, MiP’s national officer for Scotland, suggests the IJBs have allowed managers to foster a degree of innovative working. “IJBs put people in a place which is protected from health policy and from local authority policy,” she says. “People who work in them talk about being open to different ways of working and finding a non-traditional route or solution.”

But Unison’s head of bargaining for health in Scotland, Willie Duffy, is more sceptical. He argues IJBs have not delivered the closer working practices, better staff engagement and reduced duplication of effort that was promised, and warns that confusion has been created by staff working together while having different terms and conditions and operating under different management structures.

While managers in Scotland and Wales have benefitted from relatively stable structures, that is not the case in England, where the last six years alone have seen the introduction of CCGs, ICSs and STPs, the abolition of Strategic Health Authorities, and big changes to national structures – all at a time when management budgets have been cut. “The thing about England is that people don’t ever let the structures bed in – there is constant churn,” says Pullar.

On the other hand, managers in Wales may have escaped the uncertainty generated by a major reconfigurations – compulsory redundancies are almost unknown – but they can find it difficult to find time for some of the transformational work they would like to do. In particular, Crane suggests, collaborative working demands very different skills, which managers need more support to develop. “We need leadership at the top to say, this is how we are going to work, this is how we will support you, and these are the skills you need,” she says.

This is also a looming issue for the English NHS, where managers and boards are swiftly having to lose the competitive habits of decades to find win-win solutions across their health economies. As integration moves forward, it’s just one of the many lessons the English NHS has to learn from its neighbours.

Health and care in Wales

- Wales has had a relatively stable structure for the last decade, with seven local health boards responsible for delivering healthcare services within their geographical area, and some specialist trusts with all-Wales functions.

- There is no purchaser-provider split and relatively little use of the private sector.

- In April 2016, seven statutory regional partnership boards were created to drive improvements in social care services, working closely with NHS services.

- Below these regional partnerships are 22 local footprints corresponding to local authority areas in Wales. These go beyond the NHS to encompass local community and voluntary sector groups in delivering a range of health and social care services.

- Andrew Goodall, chief executive of NHS Wales, has ruled out any major structural changes for the foreseeable future.

Related News

-

The inspector falls: why the CQC needs a fresh start

After years of chaos, the Care Quality Commission urgently needs to rebuild trust and credibility with the public and the services it regulates. What needs to change and what are the priorities for new boss Sir Julian Hartley? Alison Moore reports.

-

Voice, value and vision: what analysts need from the NHS

Data analysts play a vital role in an NHS which is increasingly data-driven and focused on public health trends. But the NHS faces fierce competition for skilled analysts and many feel the health service fails to value them or fully use their talents. Alison Moore reports.

-

It ain’t what you do, it’s the way that you do it

The government’s upcoming ten year plan will try yet again to shift the NHS towards community, digital and prevention. The big question is how, writes Craig Ryan. Try honesty, patience, focusing on what matters and empowering staff and local managers—that’s what gets results.