Manage this! Covid, winter, recovery!

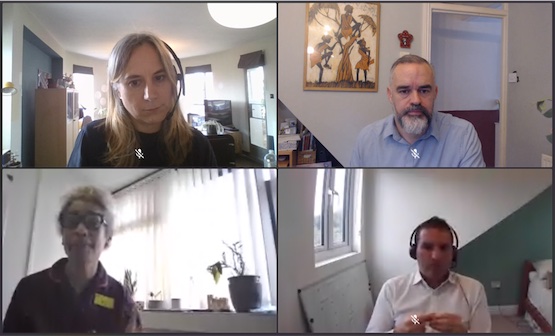

MiP Summit 2021: In the opening plenary session, Karen Bonner, Tom Simons, Jon Restell and Sarah Gorton discuss Covid, recovery, flexible working and managing under pressure.

“What I’m most proud of from the last 18 months is that when our country came calling, we were there,” Tom Simons, chief HR officer at NHS England and Improvement told MiP members at the opening session of the union’s online Summit on 8 November.

Simons joined a panel discussion, entitled ‘Manage This! Covid, Winter, Recovery!’, alongside MiP chief executive Jon Restell, who chaired the session, Karen Bonner, chief nurse at Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust, and UNISON’s head of health, Sara Gorton.

Praising “the level of innovation, determination and hard work” seen during the pandemic, Simons added: “Things that we never thought possible were made possible – by all sorts of people: staff, union colleagues and volunteers.”

But with the “the service running as hot as it’s ever run”, he warned that staff now faced the “double handed challenge” of recovering from the pandemic and reforming NHS organisations. “How do you recover your people when you’re asking them to do those two things simultaneously?” he asked.

Relentless pressure

Buckinghamshire’s Karen Bonner said: “We’ve all been personally affected, losing patients and colleagues, and I’m proud of the way everyone pulled together. But she warned that after two years of “relentless pressure”, service quality and patient safety were “definitely at risk”.

Policymakers “need to recognise that we’ve got real challenges with our workforce across the board,” she said as the “crisis with vacancies” that existed before the pandemic was likely to intensify. “I also wonder whether we’ve done enough to support managers over the last two years, because we do tend to focus so much on our clinical staff,” she added.

UNISON’s Sara Gorton said she was proud of they way unions had been able “to put authentic voice of staff to policy makers and governments” and cited the rapidly-negotiated agreement on temporary working conditions during the pandemic as an example of how unions had been “agile” in developing new ways of working during the crisis.

But she warned that many members now fear “they’re not going to be able to meet their codes of practice” and identified a number of threats to industrial relations in the NHS, including the “unhelpful” mandatory vaccination policy and “raised pay expectations” after the ending of the public sector pay freeze.

Visibility and honesty

Both Bonner and MiP’s Jon Restell warned that a lack of honest communication about the situation on the ground in the NHS risked a public backlash. “Most people in my private life think the pandemic is over,” Restell said, “so they’re beginning to look at the NHS in a business-as-usual way. And of course it’s very far from that.”

NHS England’s Tom Simons explained how, responding to the pandemic, the HR function in the NHS was evolving away from “transactional processes” like payroll towards focusing on wellbeing, staff engagement and health inequalities. These were no longer “a nice-to-have” but “critical operational issues”, he said.

“We’ve just done 1.3m risk assessments,” he added. “People used to think that was occupational health, but no longer,” he said. “You can’t sit down with a member of staff at the moment and not say ‘How are you?’ And mean it.”

Keeping our staff

Gorton urged NHS organisations to focus on retaining staff and to aim for “optimum staffing levels rather than just the bare flipping minimum”. But she warned of “difficult conversations” ahead as many jobs had changed during the pandemic and employers “may have to pay more or look at bandings to retain staff.”

She noted that “ministers have told private companies ‘if you want more staff, pay them better’” but admitted “it’s hard to see how that lesson is going to be applied to our sector.”

Bonner agreed that the NHS needed to use its existing workforce more effectively. “What is wasting their time, what is taking them away from the key elements of their job? What could be done by somebody else?” she asked.

“Despite the race and disability standards, we know we’re not doing well by many groups of people. If there’s ever a time to focus on that, this is that time,” she continued. “We have to do something about career progression [for people from disadvantaged groups]. It’s been an ongoing problem for many organisations – but what’s stopping us now?”

Restell said that while flexible working was crucial to staff retention, it was essential for managers and organisations to show that it could be work even in “difficult healthcare settings”.

Bonner added that it was important that flexible working requests were seen to be handled fairly by line managers. “Sometimes people who don’t have children and don’t request flexible working feel they’re being treated inequitably – that they’re being given all the bad shifts or the late shifts,” she explained.

Managing under pressure

Simons said NHS managers now faced “their most significant challenge in over 70 years” but wouldn’t be helped by a “macho culture” in which working long hours and at weekends were seen as a “badge of honour”.

Comparing managers to elite athletes, he added: “We wouldn’t expect Usain Bolt to run 100 metres flat out every day; athletes need time to rest and recuperate before going again. Thinking like that allows me to authorise time when I don’t read emails and weekends when I don’t think about work things.”

Karen Bonner said managers had “a personal responsibility” to look after themselves as well as their colleagues. “It’s tough working in the health service,” she said, and managers needed “to be comfortable talking about the physical and mental impact, and allow people to be vulnerable”. Managers shouldn’t try to be “superheroes”, she added: “It doesn’t matter how many hours you work, you will never get it all done. If people see you trying to do everything they think they have to do the same to keep up.

“Find things that help you to decompress – I have a yoga mat in my office that I use between meetings,” she advised. “Looking after our own personal wellbeing will make a massive difference to the people we care for.”

Gorton added: “It sounds glib, but leaders also need to have a brilliant team – and then rely on them. They need to avoid that hero complex and give people the opportunity to step up to the plate too.”

Related News

-

MiP responds to the abolition of NHS England

Government risk repeating same mistakes as Lansley by abolishing NHS England and cutting more staff from ICBs, says MiP.

-

NHS England and central staff could be cut by 50%, NHSE has announced

Government planned cuts at NHS England go much further than previously announced, with up to 50% of staff at risk.

-

New MiP survey shows growing support for principle of regulating managers, but warns it won’t improve patient safety

MiP’s member survey on regulating NHS managers shows managers are still not convinced regulation will improve patient safety or raise standards, despite growing support for it in principle.